As of 2021, there are 5.6 million Palestinian refugees and 6.6 million Syrian refugees worldwide, with both populations growing as the causes of their displacements remain unresolved.

These figures do not tell the whole story. They are limited to those refugees of each nationality who have registered with the UN (UNHCR for Syrians and UNRWA for Palestinians). It is estimated, for example, that the true number of Palestinian refugees around the world is approximately 8 million, meaning that nearly a third may be excluded from UNRWA’s oft-cited statistics.

There is another group whose experiences of displacement are also buried within these figures. As a result of the civil war, around 120,000 Palestinians have fled Syria - nearly 1 in 4 of Syria’s pre-2011 Palestinian population. As this group was already registered with UNRWA before 2011, their experiences of refugeehood twice-over are usually hidden in the official statistics. Their condition is critical to understanding displacement in the modern Middle East – and arguably, beyond it.

There has been a significant Palestinian population in Syria since the Nakba, when up to 100,000 refugees fled there from northern Palestine. With the Nakba occurring just two years after Syria formally gained independence from French Mandate rule, the Palestinian refugee crisis has been virtually contemporaneous with Syria’s modern history. The Palestinians’ plight is similarly entangled with Syria’s ongoing crisis.

Prior to 2011, Syria was regularly described as the most welcoming Arab host state for Palestinian refugees. Under Law No. 260, passed in 1956, Palestinian refugees in Syria retained their own nationality while attaining close-to-equal status with Syrian citizens in terms of social and economic rights. They could access public programs and services, own land and property (with limitation and approval by the Syrian Ministry of Interior), invest money, and establish their own businesses. While remaining stateless and without passports, Palestinian residents of Syria were entitled to travel documents that enabled them to leave and re-enter the country without requiring visas. Their situation was in stark contrast with that of their counterparts in neighboring Lebanon, where Palestinians have always been denied access to state services, forbidden from owning land, and barred from working in multiple professions.

There were, of course, limitations to the Palestinians’ almost-equal status in pre-conflict Syria. As non-citizens, they were denied the right to hold political office or vote - although the latter meant very little under the Assad regime. Like all residents of Syria, they suffered under its repression. They also experienced, on average, greater impoverishment and socio-economic insecurity than Syrian citizens. At the same time, their relative integration into Syrian society meant that Palestinian poverty and unemployment rates were consistently lower in pre-2011 Syria than in either Lebanon or Jordan.

Since 2011, the situation for Syria’s Palestinians has been upended. Previously half a million-strong, their numbers have been seriously depleted by large-scale flight from years of intensive fighting. Yarmouk, an informal camp and de facto neighborhood of Damascus that was formerly home to Syria’s most populous Palestinian community, has been besieged repeatedly, by both the Assad regime and Da’esh. The resulting deaths and flight caused its population to reportedly fall from 160,000 to just a few dozen families. As of September 10 of this year, however, the government permitted the “unconditional” return of camp residents to clear the rubble from their homes and make way to rebuild infrastructure (water, electricity, etc) - residents are required to acquire a “permission slip” that allows them to enter and exit the camp.

The devastation is not limited to Yarmouk. Since the Syrian conflict began, 280,000 Palestinians – more than half the country’s Palestinian population – have been internally displaced. UNRWA reports that more than 95% of Palestinians remaining in Syria require aid in order to meet their basic needs.

Those who have fled the country face serious problems. Despite having suffered from the same war as their Syrian neighbors, Palestinian refugees from Syria have often fallen through the gaps when it comes to aid and relief entitlements. As non-Syrians, they have regularly been unable to access relief programs designated for the country’s crisis. Most international aid efforts have been organized via UNHCR, overlooking Palestinian refugees who are registered with UNRWA.

Jordan closed its doors to Palestinians crossing from Syria in 2013, while continuing to accept Syrian citizens fleeing the same war. Palestinians who have entered Jordan since then risk deportation back to the war from which they fled. Palestinians are also excluded from living in the refugee camps established for Syrian refugees in Jordan.

While some Palestinians reacted to the Jordanian ban by seeking sanctuary in Lebanon instead, this did not last long. In 2014, Lebanon followed suit, denying entry to Palestinian refugees from Syria specifically. As a result, increasingly large numbers of Palestinians have been forced to seek sanctuary outside of UNRWA’s fields of operation, where they risk exclusion from UNHCR’s mandate and a resulting lack of support and protection. In Egypt, for example, the government bars Palestinians from registering with UNHCR, leaving them without protection or services from any UN body. Meanwhile, Palestinians in Turkey have struggled to access services, as the government does not allow UNHCR to carry out refugee status determination in the country.

These exclusions have led some Palestinian refugees from Syria to seek sanctuary further afield. While exact figures are unknown, it is estimated that upward of 60,000 Palestinians from Syria have fled to Europe in recent years, including by way of dangerous boat crossings over the Mediterranean. The same exclusions that plagued them in the Middle East have found them in Europe, where resettlement programs have largely focused on Syrian refugees, sometimes operating via UNHCR and once again denying the same rights to Palestinian refugees from Syria.

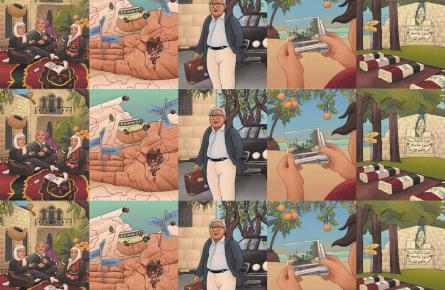

The Palestinians’ underlying dispossession lies at the root of these experiences. As a stateless people, they are distinctively disadvantaged, lacking state protection in an international system that is premised on it. Their resulting vulnerabilities can be observed in the exclusion of Palestinian refugees fleeing Syria over the last decade. Thus while the Syrian conflict is the immediate cause of their second displacement, the underlying context of their original dispossession should not be forgotten. Certainly, Palestinian refugees from Syria have been reminded of it constantly in their search for safety, as governments around the world have enacted policies highlighting their distinction from Syrian citizens.

A small number of Palestinian refugees from Syria have tried to return to Palestine itself while seeking sanctuary over the last decade. Some have travelled directly by boat to Gaza, while others fled first from Syria to Egypt, and were then deported to Gaza by the Egyptian government. While information is scarce, it is estimated that more than 200 Palestinian families from Syria have now arrived in the Gaza Strip. Their nationality no longer places them in the minority, but they, like everyone else, must contend with the ongoing blockade, impoverishment, and the constant threat of Israeli airstrikes.

Palestinians from Syria are situated at the intersection of the region’s two biggest modern refugee crises. As a community, they are now twice-refugees – and their current situation remains unstable and unprotected. More than 70 years after it started, the Nakba continues to repeat itself in different forms.